Chapter III - Inveniam Viam

|

The Senate's Demands

"I Shall Find a Way" - Control 25 settlements |

The Senate's Ambitions

Securing the Peninsula – Hold the entirety of Italia, Magna Graecia, and Cisalpina Into Africa – Hold one settlement in each of Mauretania and Africa Into Hispania – Hold one settlement in each of Tarraconensis, Cartaginensis, and Baetica Into Gallia – Hold one settlement in each of Provincia and Raetia et Noricum The Macedonian Wars – Be at war with Macedon The Protection of Rome – Have one client state |

232 BC

Summer 232 BC- The seduction of power. The desire for more. Even the common citizens in Rome’s streets felt they were destined for greater, and Rome deserved to control the world. This thought was vocalized in the Senate every day, and the patricians each announced their own schemes to expand Rome’s territory and power. The Senate was demanding that the legions must push the borders of Rome’s control yet further. Indeed, plans were commonly being based on doubling the amount of land currently held under Roman aegis.

Marcus Aurelius Tubero, head of the Julii family and commander of the VII Legion, was disturbed by the recent political events in Rome. While the Senate had been securing trade deals and treaties farther abroad, focusing on the eastern Mediterranean where they hoped to befriend Macedon’s enemies, they had been shifting there footing when dealing with closer neighbors. Pacts and trade agreements with their smaller Greek neighbors and the Celts to the north were not renewed, and the Republic clearly desired to deal with its neighbors from a more dominant role. Tubero, as any good Roman, held the belief that Rome should control the entire Italian peninsula, from the Alps to the southern coast of Sicily, but many leading figures in Rome were looking even farther afield. The most popular expansion plans, continued on past the peninsula to establishing colonies across the Mediterranean among the barbarians of Gallia and Hispania, and some even proposed reigniting the Punic War and invading Africa. Aurelius Tubero was aware that he could not quench the fires of greed and dominion, but he hoped he could at least steer their spread.

Marcus Aurelius Tubero, head of the Julii family and commander of the VII Legion, was disturbed by the recent political events in Rome. While the Senate had been securing trade deals and treaties farther abroad, focusing on the eastern Mediterranean where they hoped to befriend Macedon’s enemies, they had been shifting there footing when dealing with closer neighbors. Pacts and trade agreements with their smaller Greek neighbors and the Celts to the north were not renewed, and the Republic clearly desired to deal with its neighbors from a more dominant role. Tubero, as any good Roman, held the belief that Rome should control the entire Italian peninsula, from the Alps to the southern coast of Sicily, but many leading figures in Rome were looking even farther afield. The most popular expansion plans, continued on past the peninsula to establishing colonies across the Mediterranean among the barbarians of Gallia and Hispania, and some even proposed reigniting the Punic War and invading Africa. Aurelius Tubero was aware that he could not quench the fires of greed and dominion, but he hoped he could at least steer their spread.

Autumn 231 BC – These earthly worries were soon left behind by Tubero, as he fell ill and passed into the afterlife while recruiting in Brundisium. Leadership of the Julii fell to his cousin, Caesetius Pulvillus, who was forced to relinquish command of the VII Legion, open after the passing of General Tubero, to a leading member of the rival Cornelli. Despite these setbacks the Julii and Pulvillus, who was newly famous from his victory over the Spartan kingdom, still held dominance in the Senate with more senators under their influence than any of the other leading families.

Winter 230 BC – In a show of power and antagonism, King Antigonos of Macedon led his royal army, The Harpy’s Claws, across the disputed borders of Roman territory in Greece. His forces were poised to threaten both Apollonia and Epidamnos, and the Roman legions scrambled to prepare. As Pulvillus marched the I Legion north to assist in the upcoming defense, he ruminated on the audacity of his latest directives from Rome. With the Spartans ready to rebel at a moment’s notice, and Macedonia constantly threatening the very existence of Roman control east of the Adriatic, how could the Senate already be demanding the instigation of further wars with Rome’s neighbors?

Spring 229 BC – King Antigonos marched past the city of Apollonia, to the garrison’s great relief, and ambushed the advancing I Legion. Pulvillus had been aware that his legion would be vulnerable to such an attack while passing through Athenian territory, and would have taken advantage of the situation similarly had the positions been reversed, but he was able to do little to prepare. When the attack came, his men were so demoralized that many of his skirmishers fled the field soon after seeing the charging Macedonian cavalry. Convinced that this battle was doomed, Pulvillus had his heavy infantry form a curved defensive line on the hillside of the road, and hoped the Macedonians would recklessly charge the wall of swords and spears. Using his only mounted unit to pull a significant portion of the Macedonian hoplites away from the developing melee, Pulvillus was able to maneuver his infantry to surround and cut off the Macedonian king. When word of the king’s death in battle spread amongst the Macedonian army, the tide quickly shifted and the Macedonians soon fled the field, leaving Pulvillus with half of his legion dead or dying on the ground.

Summer 228 BC – With the death of their king, the Macedonian forces pulled away from the Roman borders, withdrawing to deal with issues of inheritance. The I Legion returned to Italia where they would recover and replenish before marching north. The Greek city-state of Massilia, a former friend and trade partner located on the southern coast of Gallia, had recently been expanding its power over the Celtic tribes across Rome’s northern border. They had interfered with and uprooted many of Rome’s trade routes in the north, including the valuable glassware imports from Patavium. Their growing influence over this normally fractured region was worrying and the Senate had decided that Massilia posed a threat that must be met. Pulvillus planned to take the I Legion into Cisalpina and contest their dominance.

Autumn 227 BC – In the Balkans, scouts reported concerning developments. Rome’s ally, the Daorsi, were being displaced by their rival tribe, the Scordisci. Their land would soon be absorbed by the new power, and Rome would have to wait and see if they favored alliance with Rome. Meanwhile, the Macedonian armies had been sighted mobilizing for a new campaign.

Winter 226 BC – To the carefully hidden surprise of Rome’s Dignitary in Pella, Tettienus Praeconinus, the Macedonian diplomats offered a peace treaty and even presented gifts of gold as a token of their sincerity. With the full knowledge that such agreements were temporary by nature, the treaty was accepted. Praeconinus later learned that the Illyrian and Celtic tribes of Antheia had rebelled and reformed the kingdom of Tylis on the Black Sea, and this had doubtlessly prompted the new Macedonian king’s desire for peace. Fortunately for him, this treaty coincided with Rome’s own aspirations to shift her military focuse elsewhere, for the moment.

Spring 225 BC – In preparation for war with Massilia, Rome’s generals felt that new tactics were needed for assaulting fortified cities. Starving their besieged opponents was a long and costly endeavor and so the Senate appreciated the need for faster methods of ensuring a city’s fall. Public funds were diverted to finding and supporting the gifted individuals necessary for Roman engineering to develop new siege engines. Soon workshops, devoted to producing the equipment needed in the construction of battering rams and war-tortoises of all sizes, would pop up in Roman cities near the frontiers.

By the end of the spring, Caesetius Pulvillus had marched the I Legion into the town of Patavium and removed the soldiers and governors from Massilia in order to occupy the province himself. Although Pulvillus claimed he was protecting Rome’s glassware trade with the local Veneti, he intended the act of aggression to be taken as a declaration of war. Not only did Rome want to keep the town and its glassworks, to the displeasure of the displaced Veneti, they soon hoped to challenge Massilian control of the rest of Cisalpina.

By the end of the spring, Caesetius Pulvillus had marched the I Legion into the town of Patavium and removed the soldiers and governors from Massilia in order to occupy the province himself. Although Pulvillus claimed he was protecting Rome’s glassware trade with the local Veneti, he intended the act of aggression to be taken as a declaration of war. Not only did Rome want to keep the town and its glassworks, to the displeasure of the displaced Veneti, they soon hoped to challenge Massilian control of the rest of Cisalpina.

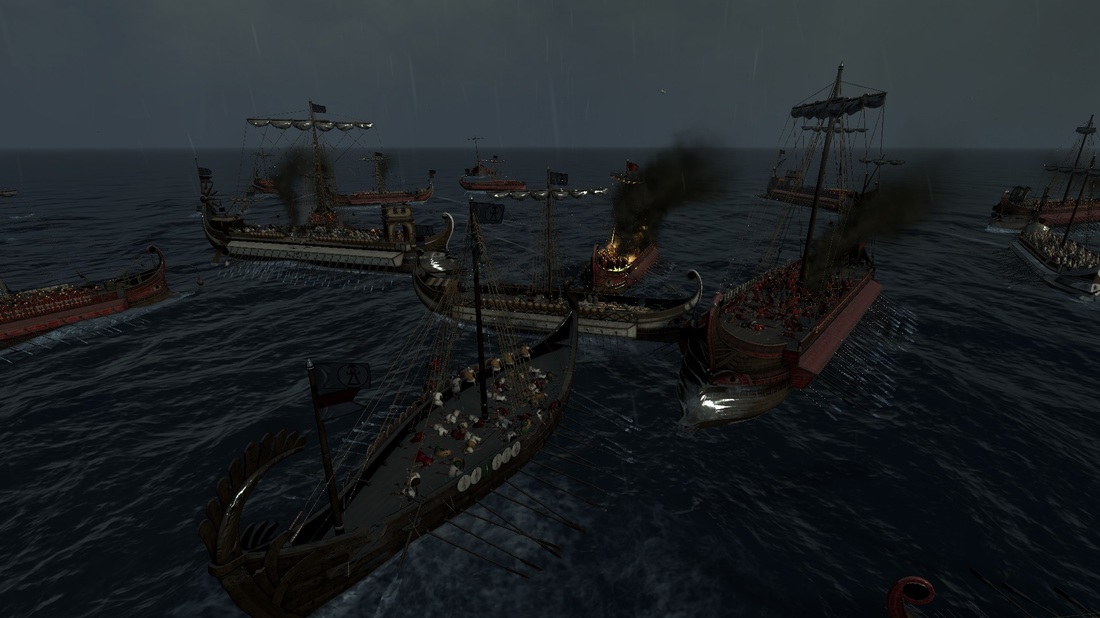

Summer 224 BC – The III Fleet, under Decimus Junius Brutus, of the Junii had been blockading the Massilian port of Genua for the past year while the Greeks had been amassing an army of their Celtic auxiliaries in the town. When they attempted to break the blockade, the ability of the new Roman navy was demonstrated. Though greatly outnumbering the Romans, the navy of Massilia had few ships worthy of combat, and the majority of the Greek and Celtic soldiers ended their lives in the waves when their transports broke under the Roman ramming prows. The III Fleet still sustained substantial casualties repelling the attack, losing two of the smaller ships from the fleet of eight to boarders and fire, and Admiral Junius Brutus died a few days later from an injury taken during the battle. Gnaeus Flamminius Costa, of the Cornelii, assumed command of the fleet and returned to Roman waters in order to reinforce. While the house of Cornelia was much less influential in the Senate, they now commanded half of Rome’s military.

Autumn 223 BC – While the I Legion was besieging the fortified town of Medhlan at the foot of the Alps, the Senate feared that Massilia would ignore the siege and strike into Italia from the village of Genua. The IV Legion marched to defend the route and guard Velathri, recruiting fresh numbers from the Latin Socii. The Senate soon tasked the IV Legion, and their new commander, Nemetorius Dentatus, with seizing the village of Genua in order to end the threat.

Winter 222 BC – As soon as the Massilian army, known as the Dread of Deimos, moved to lift the siege of Medhlan, forcing Pulvillus and I Legion to retreat back toward Patavium, The IV Legion moved in and overran the lightly defended port of Genua. The fighting was quickly throwing Cisalpina into chaos and many of the local Celts had formed warbands that raided unchecked while the Latins fought the Greeks across the province.

Spring 221 BC – With havoc continuing to reign around Medhlan, the legions spent the season quelling similar unrest in the areas of Roman occupation. The Averni, a prospering tribe in Gaul that was taking advantage of Massilia’s conflict with Rome, had raised an army around Massilia itself and threatened to sack the ancient colony and deal a crippling blow to Greek power in the region. In order to prevent this, the Dread of Deimos would likely have to abandon Cisalpina to the Romans and rebel warbands.

Across the Mediterranean, Roman diplomats watched helplessly as Carthage annexed the various tribes of Iberia and defeated the armies of Syracuse in Lilybaeum. The unchecked expansion of the Carthaginian Empire was a threat hanging over Rome, and many Senators pressed for Roman intervention.

Across the Mediterranean, Roman diplomats watched helplessly as Carthage annexed the various tribes of Iberia and defeated the armies of Syracuse in Lilybaeum. The unchecked expansion of the Carthaginian Empire was a threat hanging over Rome, and many Senators pressed for Roman intervention.

Summer 220 BC – At the Senate’s directive, the VIII Legion was founded in Genua. With the majority of Roman soldiers in Cisalpina or across the Adriatic, the patricians in Italia felt particularly vulnerable to possible invasion from Africa, and the new founding might soon be vital in a revived Punic War.

Autumn 219 BC – The Dread of Deimos returned to Massilia through the Alps and rescued the city from the Averni warband, but abandoned Cisalpina in the process. Using crude rams and ladders quickly constructed outside the walls, Pulvillus and the I Legion stormed the fortifications at Medhlan. With the town secured, Cisalpina was in Roman hands, but the Celtic, Greek, and Latin inhabitants alike were still in widespread rebellion against any authority. Particularly, the Celts of the Insubres tribe, who had be subjugated by Massilia, were reforming near Medhlan and claiming independence.

Winter 218 BC – The IV Legion, leaving Genua, pursued the Insubres through the forests of Cisalpina and caught them in the mountain pass to Octuduron. After scattering the undisciplined Celts, Nemetorius Dentatus seized the mountain town of Octuduron, nominally claimed by Massilia but abandoned and left in chaos. Dentatus, displaying resourceful ambition, realized that this village would provide an ideal foothold for Rome in the Alps and control over the mountain passes.

With their arrival on the borders of Gallia, the Romans quickly became intertwined in the maelstrom that was Celtic politics. Rome secured trade agreements and peace treaties with some bordering factions but had to settle with simply avoiding open conflict with most of the barbarian nations. While the IV Legion was embedded in the Alpine forests, the I and VIII Legions did their best to maintain the peace in Cisalpina.

With their arrival on the borders of Gallia, the Romans quickly became intertwined in the maelstrom that was Celtic politics. Rome secured trade agreements and peace treaties with some bordering factions but had to settle with simply avoiding open conflict with most of the barbarian nations. While the IV Legion was embedded in the Alpine forests, the I and VIII Legions did their best to maintain the peace in Cisalpina.

Spring 217 BC – With the establishment of Cisalpina within Roman borders, the Senate began a program of Bread and Games that drastically reduced the unrest among the starving and war-weary population. Although the success of the expensive program was undeniable, the patricians loathed diverting the tax resources in Italia that had been funding the rapid expansion of the legions and fleets. The Senate rang with debates on how long the food and entertainment would be provided and how soon the Tax Harvesting program could be reinstated in Italia.

Summer 216 BC – In Octuduron, Nemetorius Dentatus successfully led the defense of the Roman settlement against a large Celtic warband that had risen from the local populace behind a charismatic noble. The raiders had roamed the valleys unchecked, but when they attempted to drive the Latins out completely, the Celts broke upon the disciplined Roman infantry lines. Even after the narrow victory, the IV Legion continued to be heavily engaged while attempting to secure the mountain passes from the many Celtic warlords that had risen to fill the region’s power vacuum. In contrast, Cisalpina was calm for the first time in decades. The major towns were quickly coming to accept Roman rule and the I Legion departed Medhlan in order to besiege Massilia itself. Working in concert with the III Fleet, Marcus Minicius Traianus, commander of the I Legion and head of the House of Julia since the passing of Pulvillus, encircled the city to await the arrival of the Dread of Deimos. The Massilian army had seen great success against the Averni and had captured the village of Tolosa. He expected that their morale would be high and their thirst for vengeance against the Romans would be fierce.

Autumn 215 BC – At Massilia, the siege continued as both sides suffered from disease and hunger. The Dread of Deimos had been sighted in the region and Minicius Traianus anxiously anticipated an assault. Unsure of the numbers that the Massilians could bring to bear, he requested that the smaller VIII Legion, fresh with new recruits, move into a supporting position.

Winter 214 BC – When the Dread of Deimos arrived, they led a horde of Celtic warriors and Greek cavalry into the plains around Massilia. In the wide open fields, the I and VIII Legions clashed with the Dread, and the Massilian cavalry forced the Romans into a reactive stance. Unable to maneuver, the I Legion bore the brunt of the enemy charge. Traianus was forced to stretch his lines close to breaking simply to avoid being flanked, and the Roman skirmishers were unable to provide effective support without falling prey to the Massilian cavalry. As the VIII Legion moved to support the beleagured I Legion, they were slowed by the roving enemy horsemen. Weathering two waves of crushing cavalry charges, the VIII Legion slowed and destroyed the cavlary units with infantry and their own cavalry acting as anvil and hammer. By the time the VIII Legion was able to reach the Massilian flank, the I Legion’s line was crumbling and morale was hanging by a thread, but the arrival of support was met with cheers and a reinvigorated push into the Massilian lines. The VIII Legion quickly began wrapping up the flank of the Dread of Deimos and charged through their supporting units of vulnerable slingers and javlinmen. Unwilling to risk a fight to the last man, the Dread of Deimos soon fled the field, leaving mounds of dead from both sides.

Mirroring the situation on land, the III Fleet faced down a similar struggle in the Mediterranean as the Greek and Celtic ships attempted to lift the Roman blockade. Fortunately for Rome, the Massilian fleet was in poor repair and all of their ships ended the day at the bottom of the sea. The III Fleet and the I Legion accepted the surrender of Massilia’s garrison and the VIII Legion pursued the Dread of Deimos further inland, eliminating all they could find.

Mirroring the situation on land, the III Fleet faced down a similar struggle in the Mediterranean as the Greek and Celtic ships attempted to lift the Roman blockade. Fortunately for Rome, the Massilian fleet was in poor repair and all of their ships ended the day at the bottom of the sea. The III Fleet and the I Legion accepted the surrender of Massilia’s garrison and the VIII Legion pursued the Dread of Deimos further inland, eliminating all they could find.

Spring 213 BC – After spending the past year defending Octuduron from warbands of mountain tribesmen and escaped slaves, the IV Legion finally pushed the rival forces into the nearby lands of the Rugii tribe. Unfortunately, the province was far from secure and the IV Legion was commanded to remain garrisoned in the Alps.

Summer 212 BC – The Carthaginians were not only making gains in Hispania, they were also winning their long war with Syracuse. With Massilia conquered and their realm being picked apart by the tribes of Gallia, the Senate ordered the VIII Legion and the III Fleet to prepare for war in the South.

Autumn 211 BC – With no assistance from her Greek allies, Syracuse fell to the armies of Carthage. Rome girded for war, as orators cried for the liberation of the great city. The Senate could not abide Carthaginian control of Sicily, and the VII Legion was recalled from Greece in order to join the VIII Legion in an assault on the island.

Winter 210 BC – With no spies abroad to report on the events in Sicily, the legions would be entering the region blind except for the tales of travelers on the road. The Senate had provided funding for a new agent to be recruited in Cosentia, and soon Papiria Longa was providing detailed troop movements to the Roman generals. With no resistance in Gallia, the Averni and Pictones, allied Celtic tribes, invaded the former inland domains of Massilia, claiming them by might. The Greeks were no longer a player in the power struggles of Gallia.

Summer 208 BC – The second Punic War opened with the VII Legion overwhelming the unprepared occupiers of Syracuse. Liberated from the cruel control of Carthage, the city was now safely in Roman hands and General Valerius Nero settled in to regroup his army and prepare an advance on Lilybaeum. In Hispania, Veteran Antius Asellio trained the local population in guerilla warfare tactics and led a resistance effort against the Carthaginian overlords.

Winter 206 BC – The VII Legion cautiously moved towards Lilybaeum, following Longa’s guidance and fortifying their camp on the road to the market town. Their commander, Valerius Nero, was disappointed to learn that coordination with the VIII Legion and III Fleet was proving impossible, as both were trapped in the port of Karalis by the Scions of Sidon, a huge fleet from Carthage.

Spring 205 BC – Following the war’s progression from the safety of Rome, the senators recognized that the Roman fleets were still inferior to their Carthaginian adversaries. With public support, the politicians approved a requisition of funds for the construction of a new fleet in the shipyards of Syracuse. The XIII Fleet, as it would be known, would not be assembled in a day, but in the years to come might assist in breaking the stalemate in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, a Carthaginian army was poised to cross the straits into mainland Magna Graecia or reconquer Syracuse. The VII Legion maneuvered to intercept the army, called the Friends of the Hundred-and-Four, and the spy, Papiria Longa, travelling with the enemy army, was able to poison provisions that slowed the Friends’ movements to a crawl.

Meanwhile, a Carthaginian army was poised to cross the straits into mainland Magna Graecia or reconquer Syracuse. The VII Legion maneuvered to intercept the army, called the Friends of the Hundred-and-Four, and the spy, Papiria Longa, travelling with the enemy army, was able to poison provisions that slowed the Friends’ movements to a crawl.

Autumn 203 BC – With the fleets of Carthage dominating the waters and looking for an opening in which to strike, Nero and the VII Legion had been forced to maintain a defense around Syracuse instead of continuing the conquest of Magna Graecia. The Senate, frustrated with the lack of progress, even offered great monetary tribute to the family who could take Lilybaeum, but the concentration of Carthaginian forces in the area was too great. When the VII Legion had failed to catch the Friends of the Hundred-and-Four before they had crossed into the farmland around Cosentia, General Valerius Nero and the rest of the Julii were loudly blamed with failing to protect the Roman people. Although the damage caused by the enemy army before it retreated back into the sea was minor, the defamation campaign was successful, and support for the House of Julia in the Senate and among the people had fallen dramatically. At the end of the year, the Julii had dropped from dominating the majority of the senate seats to holding around one quarter. In the Mediterranean, the I Legion departed Massilia in order to support the war against Carthage by landing in Hispania and forcing the enemy to defend multiple regions.

Winter 202 BC – The I Legion occupied the settlement of Tarraco, facing only negligible resistance. Apparently, Carthage did not have the forces to spare for the defense of their domains in Hispania, but as the Romans entered the region they began to see how extensive the influence of the Averni from Gallia had become. The Celtic tribe that had assisted in the downfall of Massilia had grown to dominate many of the Iberian tribes as well, and the Roman commanders were worried about future conflict with the growing power. With only the IV Legion stationed to guard the entire northern half of the Roman territories, an attack from Gallia could prove disastrous. In preparation for such a scenario the House of Julia founded a new legion in the frontier city of Medhlan.

Summer 200 BC – While the VII Legion and the Friends of the Hundred-and-Four stared at each other from their fortified encampments outside of Syracuse, the III Fleet landed with the VIII Legion in Lilybaeum. The fleet took heavy casualties in the landing but their efforts allowed for the VIII Legion to capture the city center and rout the defenders. Unfortunately, the VIII Legion was now in danger of being cornered and forced into the sea by the Friends and their supporting forces. The VII Legion was not strong enough to break through the Carthaginian fortifications and would not be able to support the VIII Legion at Lilybaeum. The Patrician, Tettienus Praeconinus, traveling with the VII Legion sought to prevent this catastrophe by engaging some of the enemy generals in a parlay that undermined the authority of the Carthaginian leaders. With part of the enemy forces paralyzed by the subsequent negotiations and indecision, the Roman’s waited to see what opportunities would present themselves.

Autumn 199 BC – The armies of Carthage failed to act and the Roman legions were able to mobilize and assault the entrenched enemy by autumn. The Romans fielded more men in the ensuing battle than they had ever before displayed, and the surrounded Punic forces were demolished. When the commanders of the two legions met, talk quickly fell to how they would transport so many captured men to the slave markets in Rome.

In Hispania, Vipstanus Structus, the newest member of the Julii to take control of the I Legion, was unable to forward the conquest of Hispania because of unrest in Tarraco. His legion was instead relegated to garrison duties in the barbarian settlement. In order to combat growing unrest in Rome’s other occupied territories, edicts promoting Romanization and careers in the military for foreigners were started in Magna Graecia, while the Bread and Games program was renewed along the northern borders.

In Hispania, Vipstanus Structus, the newest member of the Julii to take control of the I Legion, was unable to forward the conquest of Hispania because of unrest in Tarraco. His legion was instead relegated to garrison duties in the barbarian settlement. In order to combat growing unrest in Rome’s other occupied territories, edicts promoting Romanization and careers in the military for foreigners were started in Magna Graecia, while the Bread and Games program was renewed along the northern borders.

Spring 197 BC – With the III and IX Fleets actively keeping the Carthaginians from landing on the coast of Sicily, the VIII Legion departed Magna Graecia for the long trip toward Hispania. The I Legion was still in Tarraco, where attempts at pacifying the local Iberians were failing, and the legion was preparing for a revolt. Ironically, a Celtic tribe in the Alps, the Raeti, had agreed to pay tribute to the Romans as a client state. Their desire to join with the Roman Republic was fueled by their fear of the Germanic tribes to their north, and the Romans would attempt to help the Celtic tribe if their territories were threatened.

Winter 194 BC – In Hispania, the I Legion finally marched south once again, occupying the abandoned Carthaginian settlement of Arse while the III Fleet escorted the VIII Legion through the Balearic Isles. The Roman fleet’s goal was the Carthaginian base of Ibossim, where they hoped to further capitalize on the reeling Punic nation. However, events in the North had turned against the Romans. The Breuci, a Celtic tribe that had overran parts of the Alps was now invading Cisalpina and threatening the town of Patavium. The IV and X Legion force-marched to defend the town, recruiting local Celtic mercenaries along the way, but the barbarians were advancing fast.

Spring 193 BC – No Roman army had ever experienced a more harrowing blooding than the X Legion did at the start of the new year. Ambushed in the winter storms near Patavium, the X Legion’s soldiers fought in knee-high snow that slowed the battle to an exhausting massacre on both sides. Driving the Breuci back with staggering costs, the X Legion immerged from the battle with less than half their troops remaining. General Marcus Flavinius Varro lay with the rest of the dead, and his honorable death would become a legend among the X Legion’s men.

In the Baleares, the III Fleet assaulted Ibossim. The combined strength of the III and VIII easily overwhelmed the island's defenders, and the Romans razed the settlement to the ground while massacring many of the Carthaginian inhabitants. From the ruins, new construction would soon be seen with Roman architecture.

In the Baleares, the III Fleet assaulted Ibossim. The combined strength of the III and VIII easily overwhelmed the island's defenders, and the Romans razed the settlement to the ground while massacring many of the Carthaginian inhabitants. From the ruins, new construction would soon be seen with Roman architecture.

Autumn 191 BC – At Octuduron, the X Legion again met with the Breuci. After they had been stopped at Patavium, a second warband had defeated and displaced the Raeti tribe before continuing through the Alps to assault Octuduron. The X Legion arrived first and expertly repelled the barbarians, making use of lessons learned at Patavium.

Winter 190 BC – After repelling a small fleet of ships sent to retake Ibossim, the III Fleet sailed to assist the VIII Legion in the conquest of the important port city, Qart Hadasht. When the Romans realized they would be unable to land in the port without taking horrendous casualties, the commanders decided to retreat, yielding the day to Carthage. The VIII Legion would not be leaving Hispania, to the disappointment of Qart Hadasht’s defenders, and would instead start the construction of siege engines that would allow the legion to bring their numbers to bear on the city’s walls.

Spring 189 BC – As promised, the VIII Legion returned to Qart Hadasht, supported by the III Fleet. The legion scaled the city walls with ladders, while the fleet simultaneously landed ships in the city harbor. Although both forces sustained high casualties, the Romans were able to cut down the defenders of Qart Hadasht and proceeded to raze Carthage’s primary foothold in Hispania. The III and VIII were both developing reputations as merciless killers and destroyers, causing terror in their opponents and leaving ruins in their wake.

Summer 188 BC – Left undefended while the I Legion hunted Carthaginian raiders in the hills and forests of Hispania’s inland, local Iberian tribesmen seized control of the settlement at Arse. Unhappy with Roman and Punic subjugation, the Iberian tribes had banded under one called the Edetani, and asserted their own independence. The commander of the I Legion, Sextus Vipstanus Structus, knew that there were more vital uses for his legion than chasing raiders through the woods and quelling unrest in the backwaters of Hispania, and so he met with the Edetani’s leaders. In exchange for promises of trade and a large sum of gold, the I Legion would leave the Edetani in peace, for a time. Structus then marched his army south towards the realms of Carthage.

Spring 185 BC – The I Legion met the IX Fleet on the shores of Cartaginensis and, together, they sailed towards the Straits of Hercules. The Straits, also known as the Pillars, were the opening to the Atlantic from the Mediterranean, and valuable for trade sailing around the Iberian Peninsula. They had been held by Carthage for as long as most could remember, but recently a federation of Celtic and Iberian tribes from central Hispania, displaced by the Averni conquest of the area, had overrun the Carthaginian governors. The Senate, not trusting this federation any more than Carthage, desired control of the Straits for Rome, and so Structus intended to seize the prize himself.

Autumn 183 BC - The IX Fleet easily occupied the port of Tingis, but the countryside was held by competing armies from Iberia and Carthage. It looked like Tingis might be impossible to hold without a legion permanently garrisoning the city. With the Senate already demanding that the IX Fleet attend to threats from Carthage around the Mediterranean islands, this seemed an unlikely solution. The VIII Legion, taking substantial risk by leaving the city of Qart Hadasht unguarded, marched down the southern coast of Hispania to support the I and IX at the Pillars. Meanwhile raids and incursions by the Breuci continued at the foot of the Alps. The IV and X Legions maintained control over the region, but the ancestral feud between the Breuci and Rome’s client, the Raeti, was making diplomacy impossible.

Winter 182 BC – Structus led the I Legion against a fortified camp located on the land routes through Mauretania, but the resulting battle against the Lusitani and their federation left the legion crippled, with Structus barely surviving the fight. The I Legion would not be able to continue the fight to secure the Pillars of Hercules, and would likely struggle to even hold Tingis in the near furture.

Spring 181 BC – Taking advantage of the overextended Roman military, Carthage threatened Qart Hadasht with a small army of raiders in Hispania. The III Fleet moved to protect the undefended port city, but it seemed that the enemy had expected this. As soon as the III Fleet had arrived in Qart Hadasht a large fleet from Carthage sailed into Ibossim, recapturing the settlement for the Africans.

Summer 180 BC – After establishing a Roman presence in Gadira across the strait, the VIII Legion arrived in Tingis. The battered I Legion set out for Qart Hadasht to replenish numbers and plan the reconquest of Ibossim. The VIII Legion, meeting only little more success than the I Legion, was slowly able to drive away the besieging Celtiberian warbands at tedious effort and terribly high cost. Advancing along the African coast with unfortunate timing, an army from Carthage would soon reach the city as well. Without the forces to meet them, the VIII Legion and its commander, Gnaeus Quinctius Brutus, retreated within the walls of Tingis.

Autumn 179 BC – Threatened on both sides of the Pillars, the VIII Legion decided to abandon the position at Tingis and consolidate Roman power In Hispania. Leaving Africa to be taken by the approaching Carthaginian army, the VIII Legion captured the Lusitani stronghold at Kartuba from the much diminished Federation forces by climbing the fortifications and overrunning the guards during an evening storm. There they hoped to fortify and hold the southern region of Hispania, known as Baetica. In furtherance of this goal, the III Fleet assaulted Ibossim with the support of the XII Legion, destroying the small navy left to guard the port and allowing the legion to land.

Around the Alps, Rome’s only ally and client, the Raeti, had been displaced and disenfranchised. However, their old rivals, the Breuci were not to blame. A powerful Germanic tribe, called the Rugii, had extended south into the Alps, and taken the smaller tribe’s land. The Romans in Cisalpina would have to accept the presence of their new neighbors as the vast majority of the legions were tied up in Hispania, Sicily, or Greece. Only the IV Legion remained in the North, and they were based in Patavium to discourage raids from the Breuci. Distressed by the events in the Alps, the Senate requested that the V Legion depart from their garrison duties in Epidamnos and assist in securing the northern borders.

Around the Alps, Rome’s only ally and client, the Raeti, had been displaced and disenfranchised. However, their old rivals, the Breuci were not to blame. A powerful Germanic tribe, called the Rugii, had extended south into the Alps, and taken the smaller tribe’s land. The Romans in Cisalpina would have to accept the presence of their new neighbors as the vast majority of the legions were tied up in Hispania, Sicily, or Greece. Only the IV Legion remained in the North, and they were based in Patavium to discourage raids from the Breuci. Distressed by the events in the Alps, the Senate requested that the V Legion depart from their garrison duties in Epidamnos and assist in securing the northern borders.

Winter 180 BC – Again, Carthage sent its ships against the port of Ibossim, but this time the III Fleet was there to defend. Using the natural rock formations of the port to funnel the Carthaginian ships against their largest ramming vessels, the Romans were able to destroy half of their ships before the rest retreated back towards the African shore. At Tingis, Rome was not so fortunate, and the city fell back to its former rulers.

Spring 177 BC – Struggling to maintain their hold over southern Hispania so far from the military resources of Italia and Magna Graecia, and being forced to combat the constant raiding of trade routes across the sea, the Romans pursued and concluded a peace treaty with Carthage. While the Romans would hold on to Ibossim and Qart Hadasht, they failed to control the Pillars of Hercules, and Tingis remained under the aegis of Carthage.

Summer 176 BC – With peace in Hispania, the settlements began to grow in relative security and the first steps toward a program of Romanization were taken in Baetica. The VIII and XII Legions remained in Hispania to discourage unrest in the local Iberians and to guard against the inevitable future conflict with their Punic neighbors. In Northern Hispania, the Celtic Averni had asserted their dominance among the tribes and the barbarian kingdom was closely monitored by the scouts of Rome. Their continued consolidation of the Iberian lands threatened Rome’s foothold.

In Patavium, the IV and V Legions began a massive offensive against the Breuci. Failing to understand the tenuous position in the North, the Senate had demanded the capture of the Breuci stronghold in Noreia, and had even offered a huge sum in gold to the legions if the task could be accomplished according to their deadline. Gnaeus Licinius Silanus, commander of the IV Legion and the only general in the northern theater, ignored their demands because he barely had the resources to even keep the Breuci out of Roman lands, let alone invade. The Senate’s deadline came and passed, but finally, with the arrival of the V Legion in Patavium, Silanus decided that the balance was in their favor. He eagerly marched toward Noreia, with his new siege engines trailing behind the soldiers. Meanwhile, the V Legion would eliminate the Breuci army that had been raiding the Roman borders. The Brazen Bears, as they called themselves, were currently immobilized by an unfortunate epidemic of poisoned provisions, thanks to the underhanded efforts of the Roman spy, Petronia Pulvilla. The Bears, starving and carrying their stricken warriors, had no chance of escaping back to their forests before the V Legion arrived.

In Patavium, the IV and V Legions began a massive offensive against the Breuci. Failing to understand the tenuous position in the North, the Senate had demanded the capture of the Breuci stronghold in Noreia, and had even offered a huge sum in gold to the legions if the task could be accomplished according to their deadline. Gnaeus Licinius Silanus, commander of the IV Legion and the only general in the northern theater, ignored their demands because he barely had the resources to even keep the Breuci out of Roman lands, let alone invade. The Senate’s deadline came and passed, but finally, with the arrival of the V Legion in Patavium, Silanus decided that the balance was in their favor. He eagerly marched toward Noreia, with his new siege engines trailing behind the soldiers. Meanwhile, the V Legion would eliminate the Breuci army that had been raiding the Roman borders. The Brazen Bears, as they called themselves, were currently immobilized by an unfortunate epidemic of poisoned provisions, thanks to the underhanded efforts of the Roman spy, Petronia Pulvilla. The Bears, starving and carrying their stricken warriors, had no chance of escaping back to their forests before the V Legion arrived.

Autumn 175 BC – The Brazen Bears were expertly out maneuvered and attempted to flee the field as soon as their warlord was cut down by the Illyrian cavalry of the V Legion. Very few managed to escape the massacre. The IV Legion reached the fortified town of Noreia without incident and began the siege of the city.

Spring 173 BC – With the majority of their warriors in the ground or in chains. And their largest village besieged, the chieftains of the Breuci kneeled to the Roman legions and consented to become a client state of the Republic. Disappointed to be deprived of the chance to debut his new ballistae, but grateful to be able to prevent his men from freezing to death in the oncoming winter, Licinius Silanus and the IV Legion returned to Patavium. The V Legion, on the other hand, headed south through the Breuci lands. The Macedonian kingdom, was still strong and had an iron grip over Thracia and the Athenian lands. The Romans, knowing that neither side would be satisfied with sharing power in Greece, had continued to observe and meddle in the politics of Macedonia. The Roman patrician, Septimus Ausonius Agrippa, had remained in Pella for many years to engender corruption and dissent among the local government and to promote Roman agendas, but the Senate had decided it was time for direct action. With a temporary peace across the western Mediterranean, the Senate declared war on Macedon and the legions rushed to the new front lines in Greece and the Balkans.

While the legions and fleets were stretched thin across the new domains of the Republic, many in Rome saw the peace in Hispania and the subjugation of the Breuci as a turning point in Roman foreign policy. Everyone from the slaves to the patricians were wondering where the legions would go next. No longer did the farmers in Italia fear constant invasion and Roman merchants controlled trade from Apollonia in Greece all the way to Gadira on the southern tip of Hispania. The days of Greek and Punic subjugation seemed long past and this feeling was illustrated in Rome by a Triumph held to celebrate Rome’s great families whose members had led this unprecedented expansion.

|

The Senate's Demands

"I Shall Find a Way" - Control 25 settlements (Complete) |

The Senate's Ambitions

Securing the Peninsula – Hold the entirety of Italia, Magna Graecia, and Cisalpina (Complete) Into Africa – Hold one settlement in each of Mauretania and Africa (Failed) Into Hispania – Hold one settlement in each of Tarraconensis, Cartaginensis, and Baetica (Complete) Into Gallia – Hold one settlement in each of Provincia and Raetia et Noricum (Complete) The Macedonian Wars – Be at war with Macedon (Complete) The Protection of Rome – Have one client state (Complete) |

173 BC