Chapter II - Si Vis Pacem, Para Bellum

|

The Senate's Demands

"If You Would Have Peace, Prepare for War" - Maintain 60 units |

The Senate's Ambitions

The Phoenician Colonies - Completely control Corsica et Sardinia (Complete) Establishing a Fleet - Maintain 10 naval units Naval Prowess - Research Naval Maneuvers Across the Adriatic - Hold one settlement in Illyria, Macedonia, and Hellas |

255 BC

Autumn 255 BC – The Senate and people of Rome celebrated their newfound dominance by honoring the efforts of its generals with a triumph in the capital. Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Asina and Decimus Junius Brutus featured prominently, but Lucius Julius Libo was the favorite of the masses. Perhaps due to this fame, Libo was wounded in an assassination attempt shortly after the festival, and he appointed his cousin, Tiberius Caesetius Pulvillus, commander of the I Legion.

During his recuperation, Julius Libo gained little satisfaction from observing political events developing as he had predicted years ago. Now that Rome had become master of Italia, Corsica, and Sardinia, all in the name of guaranteeing her security, she felt threatened by the strength of neighbors farther afield. The senate approved a drastic increase to the size of the Roman armies, and they commanded the legions to begin recruiting immediately.

The public seemed to be satisfied, for the moment, with their victory over Carthage in Sardinia, but they would soon turn their fear and greed east. The Greeks and Illyrians had always harassed and raided the Roman towns and trade lanes, and Greek kings had even invaded Roman lands. Now, the Senate felt Rome could control the Adriatic. The wars with the Etruscan League and Carthage had proven the need for strong Roman fleets, and part of the Senate’s new direction was to invest in the creation of a new and larger navy. With new warships protecting them at sea, the Senate had determined that Rome’s legions would be able to secure their dominance over Sardinia and Corsica and take control of key settlements along the Adriatic coast.

During his recuperation, Julius Libo gained little satisfaction from observing political events developing as he had predicted years ago. Now that Rome had become master of Italia, Corsica, and Sardinia, all in the name of guaranteeing her security, she felt threatened by the strength of neighbors farther afield. The senate approved a drastic increase to the size of the Roman armies, and they commanded the legions to begin recruiting immediately.

The public seemed to be satisfied, for the moment, with their victory over Carthage in Sardinia, but they would soon turn their fear and greed east. The Greeks and Illyrians had always harassed and raided the Roman towns and trade lanes, and Greek kings had even invaded Roman lands. Now, the Senate felt Rome could control the Adriatic. The wars with the Etruscan League and Carthage had proven the need for strong Roman fleets, and part of the Senate’s new direction was to invest in the creation of a new and larger navy. With new warships protecting them at sea, the Senate had determined that Rome’s legions would be able to secure their dominance over Sardinia and Corsica and take control of key settlements along the Adriatic coast.

Winter 254 BC – The newly founded VI Fleet, led by Admiral Spurius Norbanus Canus, was docked in Brundisium where new ships were being constructed to augment its strength. Soon they would be expected to wrest control of the Adriatic away from the Greek and Illyrian pirates with the help of the V Legion.

Spring 253 BC – Meeting with little success controlling the Etruscan and Punic populations of Corsica and Sardinia, Cornelius Scipio Asina and the IV Legion were forced to crush a large uprising led by former leaders of the Etruscan League. Even after the massacre, public order on the isles was dismal. In Brundisium, Norbanus Canus studied reports of the continuing Greek wars as he waited for the right time to strike across the sea. The balance had turned against King Pyrrhus in the war as the Athenians had joined forces with the Spartans, but the king of Epirus had again been making recent gains. Meanwhile, the Macedonians stayed aloof of the conflicts to their south, secure in their dominance of Thrace and the Balkans.

Summer 252 BC – Canus had decided the time was right. Pyrrhus was on the back foot and Norbanus Canus hoped taking the Greek king’s capitol of Apollonia would provide a perfect foothold for the legions while eliminating the power base of one of Rome’s hated enemies at the same time. The Norbanus house was only a minor family in Rome, but Canus was certain this assault would change their fortunes. Meanwhile in Rome, the Julii family had been granted leadership of the newly founded VII Legion.

Autumn 251 BC – Canus’ landing at Apollonia proceeded according to plan and the proud city was looted and torched. The Greek wars had left the city without a garrison worth mentioning, and King Pyrrhus' army was engaged with the Athenians. If the king returned to his land now, the real battle would begin and the V Legion would be put to the test.

Winter 250 BC – The V Legion wintered in Apollonia, with tension high as they fortified the city. Greek armies roamed through the hills and mountains, and any one of them might try and kick the Latins back into the sea. Across the Adriatic in Brundisium, the VII Legion prepared to make the journey to Greece as well.

Spring 249 BC – Word reached General Lucius Papirius Cursor, of the V Legion, that King Pyrrhus and his army had been defeated and scattered outside of Larissa. Without having to worry about an impending attack from the king of Epirus, the V Legion would be able to turn its attention towards neutralizing the Illyrian raiders to the north. When the VII Legion arrived in Apollonia, taking on garrison and reconstruction duties, Cursor led the V Legion up the coast, raiding as they went.

Summer 248 BC – While the V Legion raided the Illyrian coast, engaging in minor skirmishes, the Greek wars were at a lull following Pyrrhus’ demise. In Sicily, Carthage had recaptured Lilybaeum, and were once again creating fear in Rome of Carthaginian dominance in the Mediterranean.

Autumn 247 BC – After years of skirmishing and raiding, Papirius Cursor risked a pitched battle against the outnumbering forces of the Ardiaei clan. In the extended fight that ensued on the Adriatic coastline, the Roman cavalry took heavy casualties performing harassment maneuvers that kept the Ardiaei disorganized and unable to surround the Roman infantry. Most of these units were cut off from the bulk of the Roman army and collapsed under the pressure, but the death toll among the Ardiaei was far worse at the end of the day. The Balkan tribesmen retreated back into the mountains and the V Legion was able to march into the village of Epidamnos. Here, the legion began to convert the settlement into a forward base for Roman aspirations along the Adriatic.

Winter 246 BC – Having met with success on their ventures into Greek politics so far, the Senate continued to demand more control over the fragmented region. While the divided Greek city-states and kingdoms looked weak to the politicians in Rome, the commanders across the Adriatic were hesitant to provoke further conflict. If the legions invaded one Greek realm, it was likely that the others would come to their defense and the Spartan and Athenian forces were far larger than anything Rome had brought across the sea. The V and VII legions demanded further reinforcements from Italia and Magna Graecia.

Spring 245 BC – As Rome attempted to extend its influence into Greece and the Balkans, it became clear that the Macedonian kingdom was the most powerful faction in the region. They were far ahead in dominating the politics of the Greek states, and it seemed inevitable that the Romans would have to pull out of the region if the Macedonians chose to oppose them.

Summer 244 BC – The Senate had requested the construction of a new fleet at the port of Apollonia to bolster the Roman presence in the Greek Isles, but Marcus Aurelius Tubero of the Julii, commander of the VII Legion in Apollonia, declared that the funds were needed to strengthen his army. He expected that his legion, still untested in battle, would soon see conflict with the Greeks. The Spartans and Athenians had recovered from the wars against Epirus, and were displeased with the Romans controlling Apollonia. Greek armies were reported to be gathering on the road to Apollonia.

Autumn 243 BC – While focused on political aspirations to their east, the Romans accepted envoys from Carthage bearing a small tribute and offers of peace. Despite much vocal objection in the streets of Rome, the Senate decided to accept the truce. The inevitable conflict between the two cities was again delayed.

Winter 242 BC – Exposure to Greek architecture and infrastructure highlighted many of the inadequacies in Rome’s construction. The patricians of the city approved a plan for remodeling and rebuilding the densest parts of the growing city using techniques found in the East, and they announced that fitting rewards and support would be given to those who could acquire experts and examples to send back to Rome.

This new objective was the least of problems for the legions in Greece at the moment, as a large Spartan army had been spotted camping in Athenian lands on the road to Apollonia. Roman diplomats had been rebuffed from all Greek courts and forums and it appeared that they were forming a united front against the Latins. The Spartan kingdom had formed an alliance with the Macedonians and the Athenians had been forced to do the same during the wars against Epirus and now paid tribute to the much larger realm. The Romans could likely hold their ground against any one of the factions, but it appeared they may soon be fighting all three.

This new objective was the least of problems for the legions in Greece at the moment, as a large Spartan army had been spotted camping in Athenian lands on the road to Apollonia. Roman diplomats had been rebuffed from all Greek courts and forums and it appeared that they were forming a united front against the Latins. The Spartan kingdom had formed an alliance with the Macedonians and the Athenians had been forced to do the same during the wars against Epirus and now paid tribute to the much larger realm. The Romans could likely hold their ground against any one of the factions, but it appeared they may soon be fighting all three.

Spring 241 BC – Determined to remain on the initiative, the Romans struck first against the Spartan army, relying on surprise and uncertainty in the Spartan ranks to undermine their morale. Veteran Labienus Laenas was commanded to harass the scouts and flanks of the Spartan encampment to encourage the belief that the Roman army's strength and reach was greater than the Spartans expected. This did not produce the results that Aurelius Tubero had hoped for and the Spartan army remained focused on the advancing VII Legion. The attack was brutal with Spartan hoplites and Roman hastati engaged in a grinding melee that threatened to leave none standing at the end. On the flanks of the bloody scrum, the more versatile Roman skirmishers, consisting of mercenary Tarantine and Illyrian cavalry along with well-armored Greek peltasts, routed the few skirmishing units fielded by the Spartan army. The Roman skirmishers were then able to wrap around the tightly packed units of pikemen and hoplites that were giving no ground to the Roman infantry and threaten the Spartan commander while attacking the undefended sides of the Spartan units. Surrounded, the Spartan units on the flanks were the first to cave, starting a domino trend that routed the Spartan army from the field. The Spartan commander and his Royal Hoplites were the last to fall, fighting to the end instead of fleeing.

The VII legion had lost almost half of its fighting strength in the battle and Tubero turned the army back towards Apollonia rather than continuing into hostile Greek territory. Further north, Cursor Papirius, commander of the V Legion, implemented a treaty of trade and non-aggression with the Illyrian tribe of Daorsi. The Daorsi were at war with the Macedonians and Papirius believed that the enemy of his enemy could be a worthwhile friend.

The VII legion had lost almost half of its fighting strength in the battle and Tubero turned the army back towards Apollonia rather than continuing into hostile Greek territory. Further north, Cursor Papirius, commander of the V Legion, implemented a treaty of trade and non-aggression with the Illyrian tribe of Daorsi. The Daorsi were at war with the Macedonians and Papirius believed that the enemy of his enemy could be a worthwhile friend.

Summer 240 BC – Accepting the risk of leaving the northern Roman borders unpatrolled against barbarian incursions, the I Legion force-marched south to set sail toward Apollonia, where Tubero had formulated a new plan of attack. The Athenians seemed content to allow their two stronger neighbors to field the armies for the current war effort, and they likely saw the war as an opportunity to advance the strength of their own position in Greek politics. Tubero did not wish to antagonize the Athenians and decided that an invasion through their territory was not ideal. The Macedonian kingdom to the north was the biggest threat to Rome’s position on the western coast of Greece, but they were currently engaged in other wars and disputes against various Illyrian tribes. Tubero determined that the best course of action was to take this opportunity to eliminate Sparta while her allies were unable, or unwilling, to combine efforts and to do so without crossing through Athenian territory.

Autumn 239 BC – At Epidamnos, on the Adriatic coast, reports arrived that a massive Macedonian force had defeated a warband of the Daorsi and now approached the Roman settlement. Bribes of peace were offered to the army’s commander, Demetrius, but these were refused. In Apollonia, the commanders of the I and VII Legion, cousins in the Julii family, worked with the VI Fleet to create a plan for enacting the attack on Sparta while preparing for the defense of Epidamnos. The I Legion, still under Tiberius Caesetius Pulvillus while Julius Libo remained in Rome to represent the family, would be escorted by the VI Fleet to the southern coast of Greece where they would attempt to land and encircle the city. The VII Legion would march all the remaining forces available in Apollonia to the defense of Epidamnos.

Winter 238 BC – The Macedonian army remained in the mountain passes all season. The Daori spies had somehow poisoned the army’s supplies and Demetrius was forced to camp his starving men as they waited for further stockpiles to be assembled. Unfortunately for the Romans, an additional smaller Macedonian force had appeared and threatened Apollonia. Tubero left the majority of his men with the V Legion in Epidamnos, as he returned to Apollonia in order to organize a defense. Meanwhile, Rome’s spy and representative, Caelia Turda, who had been searching for potential allies in the conflict against Macedonia, had established connections with many of the Greek kingdoms in Asia Minor. None would commit soldiers to the cause, but many trade agreements and promises of financial support were secured.

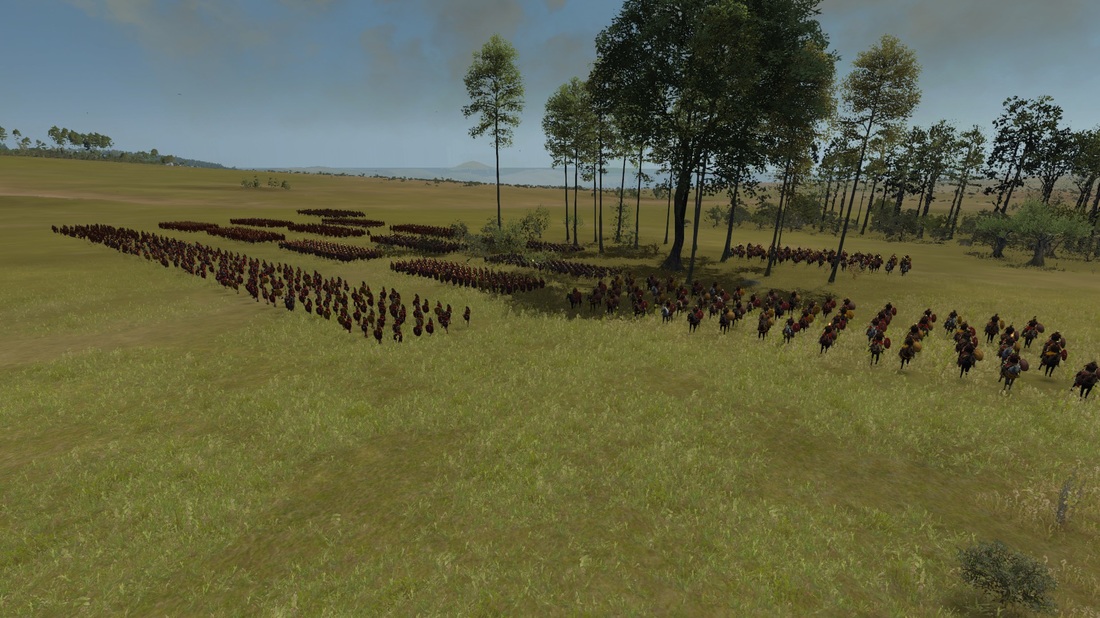

Spring 237 BC – The Macedonian army had been unable to secure new supplies, thanks to further sabotage from the Daorsi spies, and was starving in the mountain pass. Pacuvius Canuleius Messalla, commander of the V Legion in Epidamnos and a member of House Junia, decided this was an opportunity he could not pass up. He had mustered as many men as was available in the region and the Macedonian army was demoralized and uncertain. Rome could ill afford to maintain the huge garrison that had been organized at Epidamnos, and so Messalla attacked the Macedonian encampment with the Senate’s approval. Demetrius Kalos, expecting to wait for reinforcements and supplies, was caught off guard by the numbers Rome had been able to muster within the past year. The roman cavalry, supported by numerous Illyrian auxiliaries, was able to rout the vaunted Macedonian horsemen and the rest of Demetrius' starving force was surrounded and destroyed. The few survivors fled into the mountains.

Summer 236 BC - In the Roman Senate, debates were raging around the benefits of expanding Roman influence across the Adriatic. The cost of the war in Greece was immense, even with the successful adaptation of Tax Harvesting edicts in Italia providing additional funding. Roman technology and engineering had benefitted from the access to Greek knowledge and expertise, and the Senate decided that a more diplomatic approach should be explored in future dealings with the Greek nations. In accordance with this decree, the Senate recruited the patrician Gaius Tettienus Praeconinus in Apollonia as Rome’s first official Foreign Dignitary. He would work in concert with the legions to further Rome’s influence in a quicker and hopefully cheaper manner.

Autumn 235 BC – In Apollonia, Marcus Aurelius Tubero received words of the death of Lucius Julius Libo. Tubero was now the senior political figure in the House of Julii and inherited much of his responsibilities. Meanwhile, another member of the Julii house landed with the I Legion on the coast near Sparta. Caesetius Pulvillus was fielding a large and expensive army of Roman heavy infantry and skirmishers supplemented by Tarantine and Cretan mercenaries he had contracted while sailing through the Greek islands. Knowing time was on the Spartan's side, he was eager to attack the Spartans. Veteran Laenus had landed his retinue in Spartan territory the previous year, but his attempts at demoralizing the Spartan defenders, utilizing guerilla tactics in the countryside, seemed to have had little effect on the enemy garrison. Pulvillus knew that a direct assault was too risky and decided that he would attempt to lure the Spartans into a location of his choosing.

Winter 234 BC – The army Sparta had raised in its defense was vast, disciplined, and well-armed. Pulvillus acknowledged his force would not survive the direct assault he longed for, and instead he raided the Spartan countryside and fled from the enemy army when it arrived. Finally, during the winter, he saw an opportunity. A third of the enemy army had marched north, most likely to threaten poorly defended Apollonia, and the bulk of the Spartan army had marched far enough away from Sparta to preclude the arrival of reinforcements in the event of a battle. The Spartans, confident in their strength, were travelling fast in their pursuit of Pulvillus, and were neglecting to scout their advance properly. With Laenus’ guerilla tactics already distracting the foe, the I Legion set an ambush for the pursuing force. Using a gorge to funnel the Spartan army, Pulvillus sprung an attack on the unprepared enemy, and crushed the supporting units of skirmishers and cavalry before they could contribute in the fight. With his cavalry and hastati eliminating the support troops in the rear of the line. Pulvillus whittled the Spartan heavy infantry with a constant barrage of arrows and javelins from the rim of the gorge. By the time the Spartan hoplites were able to engage the Roman infantry, they were a shadow of their former strength. The famous Spartan morale that had frustrated the advance of the Roman legions so far, broke under the pressure, and most of the army quickly fled the ambush when they realized how completely they had been out-maneuvered. With their army scattered for the moment, the I Legion was able to occupy Sparta itself with little opposition.

Spring 233 BC – The Romans now held Sparta and the southern tip of the Greek peninsula, Apollonia on the west coast, and Epidamnos further up the Adriatic. Macedonia still contested the Roman presence, but with Sparta pacified, the Senate felt confident that their newfound hold on the Adriatic Sea was secure. More important to the Senate was the fact that the Roman legions and fleets had never been larger or of higher quality. The conflicts with Carthage had taught the Roman’s how to craft better ships and maintain a true fleet, and the war in Greece had shown them the worth of a disciplined, drilled, and physically conditioned army. The Roman military would force their great rivals in Macedonia and Carthage to accept them as equals in the power struggles of the Mediterranean, and no longer as an upstart republic to be bullied into submission.

The conquest of Sparta was hailed as a landmark achievement by the leaders of Rome that proved the strength of their legions, and the city celebrated with games and parades. All of the legions sent honor guards home to participate in the ceremonies, and they displayed captive enemies and looted treasure to the delighted roar of the plebeians. It was obvious to all that Rome's new prosperity was rooted in her legions and fleets, both much stronger than ever before thanks to the aggressive policies of her senators and generals.

The conquest of Sparta was hailed as a landmark achievement by the leaders of Rome that proved the strength of their legions, and the city celebrated with games and parades. All of the legions sent honor guards home to participate in the ceremonies, and they displayed captive enemies and looted treasure to the delighted roar of the plebeians. It was obvious to all that Rome's new prosperity was rooted in her legions and fleets, both much stronger than ever before thanks to the aggressive policies of her senators and generals.

|

The Senate's Demands

"If You Would Have Peace, Prepare for War" - Maintain 60 units (Complete) |

The Senate's Ambitions

The Phoenician Colonies - Completely control Corsica et Sardinia (Complete) Establishing a Fleet - Maintain 10 naval units (Complete) Naval Prowess - Research Naval Maneuvers (Complete) Across the Adriatic - Hold one settlement in Illyria, Macedonia, and Hellas (Complete) |

233 BC